In July of 2024, we lost Dr. Bernice Catherine Harper. Our sadness is tempered by our overwhelming gratitude for Dr. Harper’s immeasurable contributions to palliative care throughout the world. As many of you know, she was instrumental in the development of the Foundation for Hospices in Sub-Saharan Africa (FHSSA), the precursor organization to Global Partners in Care. Her ongoing engagement over the years provided guidance and wise counsel for our work.

Dr. Harper was not only a driving force who had a profound impact on the organization and the many lives we’ve touched – she was a close friend, confidant and advisor who will be greatly missed and forever appreciated.

This article was written and published in February 2022 as a tribute to Dr. Harper on the eve of her 100th birthday. She worked closely with us to create it and was delighted to share more of her life story. We hope it serves as a reminder of her many achievements for those who knew her, an introduction for those who didn’t and an inspiration for all. She emanated faith, compassion and a conviction that we must care for one another. She continues to inspire us!

To Care for the Dying, First Love and Care for the Living

The world is filled with remarkable people – leaders and heroes whose values guide them to place the needs of others above their own, who strive for the betterment of others, and who use their strength to fight for those in need. Social media and news outlets share stories of these heroes and heroines, but there are many more of these humble leaders who do not receive mainstream recognition for their contributions.

This is the story of one such woman – one whose life has been dedicated to those in need – and her many contributions. This is a woman who has chosen a life of service over a life of comfort; a woman who never backs down when faced with adversity. This is a woman who fulfilled her childhood dream of becoming a missionary to Africa. This is a strong, compassionate, resilient woman who has dedicated her life’s work to ensuring all people have access to a comfortable and dignified death. Dr. Bernice Catherine Harper, MSW, MScPH, LLD, who turns 100 this month, recently reflected on the history of Global Partners in Care (formerly the Foundation for Hospices in Sub-Saharan Africa) along with her own history as a pioneer in the field of social work and hospice care.

UPBRINGING AND EDUCATION

Bernice Ola Catherine Wright (Harper) was born in Covington, VA. She grew up in a family of 12 in a segregated society, and there was no room for complaints or self-pity; Harper learned at an early age to control what she calls her “TNT” (tears and temper). “I had a terrible temper. How else would I survive in a family of 12?!” From a young age, Harper learned to carry herself with dignity and stood up for what she believed in. She came to the conclusion early in life that the integrity of an individual is irrelevant to the color of their skin. Harper learned to see beyond outward appearances and to love each person for whom they truly are — a conviction she cultivated in all aspects of her life. While her brothers and sisters hoped to one day live and work in New York or Washington DC, Harper set her heart on becoming a missionary to Africa. She was just eight years old at the time, and she had no idea where Africa was located. Her neighbors called her “the little missionary” because she would frequently walk children to Sunday school, take care of the sick and help others with their daily needs. Little did she know that her passion for helping others would propel her to a life of service that would indeed one day take root in Africa.

Caring for others was always central for Harper, yet she also recognized her own self-worth. She quit her first job, cleaning rooms and mopping kitchens, at the age of 10. “I worked hard and she paid me 10 cents. I told my mother I’m not going to work for her anymore – I worked all day and she only gave me a dime, and I’m worth more than that.”

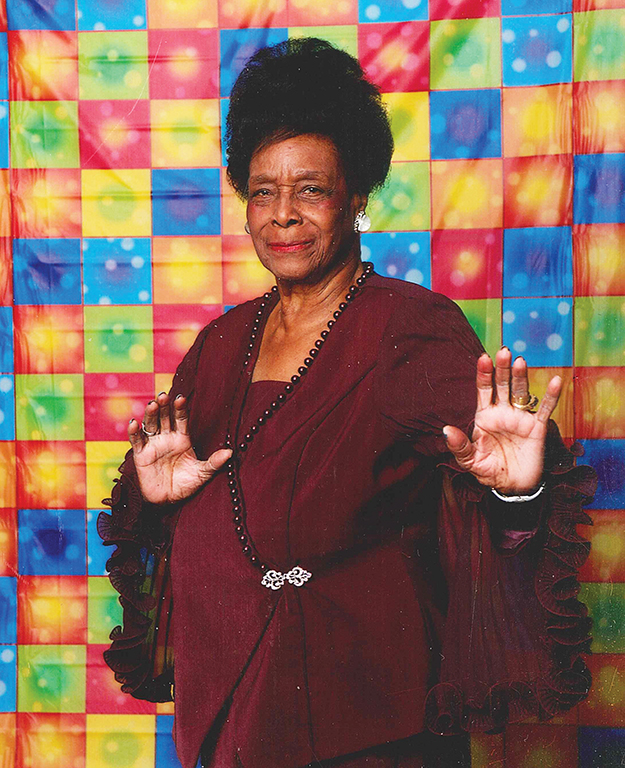

Dr. Harper at a Capital Caring Annual Meeting

Dr. Harper addresses the Southern Africa AIDS Care Training Council in Zimbabwe, 1996.

Faith was an important part of Harper’s upbringing, and her family was very involved in their church. Harper also learned a lot from watching her mother and father manage such a big family. She credits “God, family and church” as the bedrock of her upbringing and the foundation of her leadership skills.

When Harper made the decision to attend college, she was the only one in her family who thought it was possible. Her siblings had exhausted all of the family college funds, so Harper took initiative to find another way. She received a scholarship to cover tuition at Virginia State College, but not room and board. She needed a workstudy position to cover this cost. On a visit to campus, she marched into the office of the president and asked to work in his home to help cover this expense. He admired her tenacity, but that position was filled. He promised to contact her if the other person didn’t work out – which was exactly what happened. Harper ended up cooking and cleaning for the president and his wife during all four years of college. She attended classes during the day, cooked and cleaned in the evening and still managed to find time to study.

Harper earned her undergraduate degree from Virginia State College in 1945 with majors in education and psychology. She was a proud member of the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority. Virginia State College was the only public institution for Black people in a segregated Virginia and they did not offer many graduate degrees, so Harper went to California to pursue a master’s degree at the University of Southern California’s (USC) Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work. She still faced racism in California, but became one of the first out-of-state students to receive a Master of Social Work (MSW) from USC in 1948. Ten years later, she further broke barriers by earning a Master of Science in public health (MScPH) from Harvard University. She was among the first Black women to do so. Finally, Harper earned an honorary Doctorate of Law from Faith Grant College in Birmingham, AL in 1994.

Dr. Harper (second from right) with nurses from Island Hospice in Harare, Zimbabwe, 1996.

Dr. Harper with Ruth Knee, a founder of NASW and national leader in social work.

Dr. Harper waves “hello” during her visit to South Africa.

EARLY WORK

Harper’s professional career began at the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles after earning her MSW from USC. She worked with children who had asthma for 10 years and served in a total of nine different clinics and two hospital wards. Harper worked for the City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, CA from 1961 to 1976. She started as a home care coordinator and briefly left in 1969 to earn her MScPH from Harvard. Returning with a new skill set helped her implement improved practices within the organization and she was ultimately promoted to chief social worker and director of the social work department. Harper was not only good at her job of caring for patients and families, but she had a knack for organization and efficiency. By listening to the needs of the families and patients, she was able to help improve admission and discharge practices and cut down on the time and burden for patients.

During this time, Harper recognized the need to train social workers to better cope with the anxieties and professional grief that resulted from their demanding responsibilities. Harper authored the book Death: The Coping Mechanism of the Health Professional in 1977. She published two subsequent books to share her experiences with death and overcoming the stresses of being a social worker. Harper dedicated her final book to health professionals and their families. She states, “This final book is about us: health professionals, our families, our death and our dying…” Harper believes that in order to understand how to deal with death and dying, one must first recognize who they are in the healthcare field and their own feelings about death and dying. Learning to love and care for the living is also a prerequisite to serving the dying. The book received a “Better Life” award from the American Health Care Association, and her findings are still being utilized by healthcare and hospice professionals today.

GLOBAL IMPACT

Harper spent the next “35 years, 11 months and 23 days of service” as a medical care advisor in the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). When she first arrived in government, Harper quickly realized that much needed to be done to support a variety of medical fields. She wasted no time in integrating social work into numerous proposals. On one occasion, after Harper presented 17 proposals to her colleagues, someone asked why she recommended allocating so much money ($236,000) for social work. Harper recalled that her audience was so quiet “you could hear a pin drop in the room.” Perhaps there was a backstory here, but Harper wasn’t bothered by that and got straight to the point, “because the conditions of patients and the needs of families require that kind of care.” Ultimately, all of the proposals passed. Of her many successes in government, Harper is best known for her advocacy for the integration of hospice care benefits into Medicare. Harper’s recommendations included the incorporation of physicians’ services, nursing care, medical social services and counseling into the Medicare package. Legislation to allocate Medicare funding for hospice care was officially passed in 1982.

Despite her distinguished career in the United States (US), Harper maintained her passion for missionary work in Africa. Harper had always fought for the rights of people to access healthcare and to have a dignified death, especially for those in great need. She served as chair of the National Hospice Organization Task Force on Access to Hospice Care by Minority Groups for 10 years. In 1996, Harper received the opportunity to represent the US in the first professional seminar tour of hospices in South Africa and Zimbabwe — a defining moment in her life. Although she was invited as a representative of the government, HHS did not avail funding to support her engagement, so Harper used her vacation time and her personal credit card to take herself to Africa with a group of other hospice leaders from the US. Throughout her visit, Harper conducted workshops and presentations regarding both her book and social work experience to share her expertise on death and dying.

“We are a global world. It has been said that we should love our neighbors as ourselves. But the word neighbor means everyone under the sound of your voice, and voices are world-wide now. In a moment you can flash a word, a sentence, a comment around the world and you can show your face in that same amount of time. So we are a global world and it says to me that as a global world we love our neighbors as ourselves and we utilize our skills, and our knowledge, and our resources and we become what I like to call soldiers of caring. Soldiers of caring to help people throughout the world.”

Dr. Bernice Catherine Harper

Dr. Harper interacted with many influential individuals throughout her career,

including former Senator Bob Dole and First Lady Barbara Bush.

During this time, the HIV/AIDS pandemic was in full force in sub-Saharan Africa. The few hospices operating there were adapting to the needs of people living with HIV and AIDS. The limited number of hospice programs and minimal supplies of pain medication could not support the growing body of patients. Healthcare systems quickly became overwhelmed. Harper recalls a chilling remark echoed by an African colleague during her visit: “Africa is becoming a graveyard.” Recognizing a need to support Africa’s hospice and palliative care programs, Harper and her colleagues formed the Foundation for Hospices in Sub-Saharan Africa (FHSSA) in 1999 with the goal to partner hospice and palliative care organizations in the US with those in sub-Saharan Africa to foster knowledge exchange and resource mobilization.

While this experience may not fit the typical missionary meaning, Harper and her colleagues have certainly left a mark on the African continent. Over the years, FHSSA established more than 100 of these twinned partnerships. Harper has since stated that she achieved her childhood dream. But her influence has not stopped in Africa. Her legacy continues to live on through FHSSA, which later expanded its work beyond Africa to other parts of the world and is now known as Global Partners in Care (GPIC). The foundational work of Harper and her co-founders has created a global impact that inspires organizations, healthcare providers and community members around the world to ensure access to compassionate care for those who need it most.

A LASTING LEGACY

Harper retired in 2006 but continues her legacy of leadership. She holds positions on the US Steering Committee of the International Council of Social Welfare and the Board of National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Pioneers. Harper is also a member of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization’s (NHPCO) Diversity Advisory Council, which she helped establish. Early in her career, Harper was selected by the League of Women as one of the 11 “Women of Tomorrow.” She is the first recipient of the NASW Foundation’s Knee/Wittman Outstanding Achievement Award in Health/Mental Health Policy. Harper received the US Health and Human Services Department’s Distinguished Service Award and was inducted into the California Social Work Hall of Distinction in 2017.

Education has always been important to Harper. She believes we have a responsibility to use our skills, knowledge and resources to deploy “soldiers of caring” to help people throughout the world. Together with NASW, FHSSA raised funds to establish a scholarship fund in Harper’s honor to support the palliative care education of social workers in Africa. GPIC continues to manage the fund today in collaboration with the African Palliative Care Association (APCA). Harper also worked with Capital Caring, one of the oldest and largest non-profit hospice and palliative care providers in the US, to set up a scholarship fund in her name to help train social workers in this country.

Dr. Harper with Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Dr. Richard Payne in California, 2001.

Dr. Harper was the keynote speaker at Capital Caring’s 40th Anniversary Annual Meeting.

Harper’s professional career holds no shortage of profound achievements. From ensuring hospice benefits for Americans to extending aid to hospice and palliative care services in Africa, Harper is truly a pioneer of social work and palliative care. Perhaps what is most impressive of all is the driving force that carried her through a lifetime of service: her character. Harper’s character — dignified, passionate, resilient, loving — is more memorable than any accomplishment or award. Her leadership, which inspires change in a variety of settings —community, federally, globally — is equally empowering. Those who are fortunate enough to meet her and listen to her speak will quickly realize that Harper, at 100 years young, still radiates a scintillating desire to help others.

Harper believes that we should all be “soldiers of caring” – combining devotion and compassion in caring for one another. This juxtaposition of a strong soldier who provides loving care is the embodiment of Harper’s character. She faced adversity throughout her life, but she never let it stop her from achieving her goals. “In order to be a social worker, you must love all people,” she said. This is a mentality that everyone — not just social workers — should strive for. If we want to end human suffering around the world, we must be strong and compassionate in our efforts to care and advocate for those who are too weak to support themselves. Harper continues to advocate for awareness and support for the terminally ill and dying to set the stage for future generations; she believes each generation has a moral duty to care for the next.

Dr. Harper with members of the founding FHSSA board of directors and other colleagues.

When asked about the global need for aid despite facing a number of challenges within our own country, Harper said, “We should love our neighbors as [we love] ourselves. We may look and talk differently, have varying levels of wealth and development, or live on the other side of the world, but we are all neighbors.”

Indeed, there are obstacles within every country, but we must not forget that we are all members of the human race. “Our skills, knowledge and resources can be shared around the world quicker than ever before. Our voices can be heard from miles away. Our love for each other can be felt across oceans. We are all neighbors, and we must look out for one another. We must stand up and fight to end human suffering, together.

African Palliative Care Education Scholarship Fund

Each year, APCA and GPIC provide a limited number of scholarships for palliative care training opportunities. The fund was established in 2011 by generous donations from the National Association of Social Workers in honor of Dr. Bernice Catherine Harper and from an anonymous donor in honor of the palliative care service of Katherine Defilippi, a nurse from South Africa. If you would like to make a donation to the Scholarship Fund in memory of Dr. Harper, please do so below.